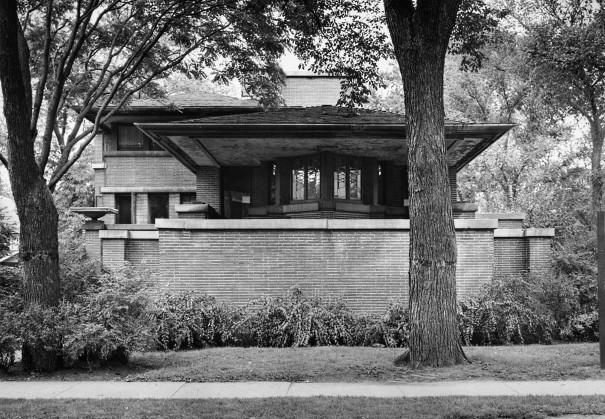

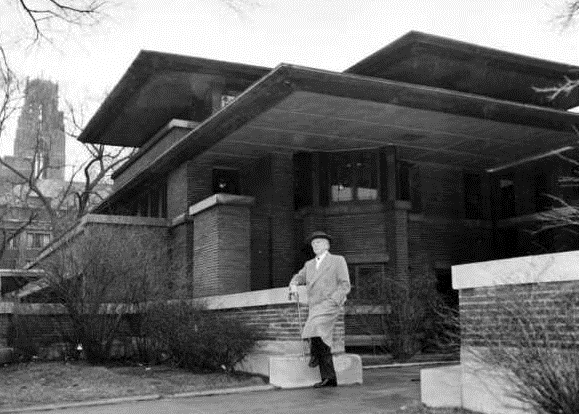

When Frederick Robie commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design a home for him and his growing family in 1908, neither man knew that the home’s iconic design would become the celebrated jewel that it is today. Considered by many architectural scholars to be one of the most influential and important residential designs of the 20th century, Wright’s Robie House is the pinnacle expression of his Prairie Style, exhibiting all of the style’s hallmark design elements in a harmonious, organic form that pleases the eye, while also making an aggressive architectural statement.

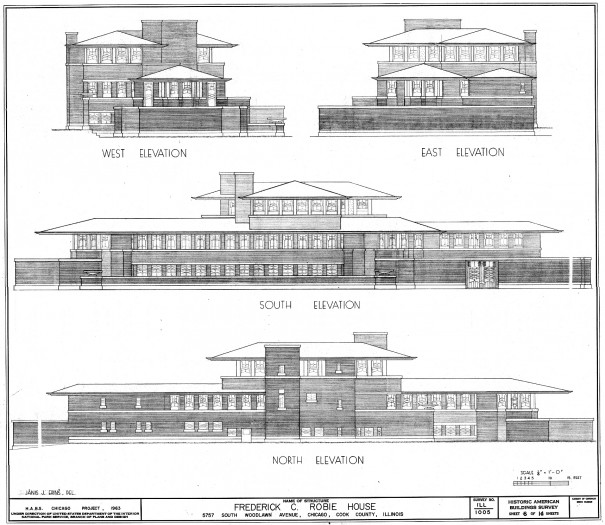

Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), August 1963. National Parks Service (Public Domain)

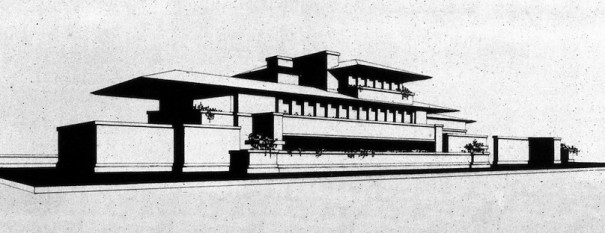

Viewed from any angle, the Robie House is imposing. And when you consider what typical residential architecture looked like in 1908, it’s not hard to see how much of a radical departure this home would have been. One of its most eye-catching features, a massive cantilevered overhang on its west end (above and below), extends an incredible ten feet from the closest wall and a staggering 21 feet from the nearest structural masonry pier. But there’s much more to this home than just gravity-defying cantilevers…

Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), August 1963. National Parks Service (Public Domain)

An executive at the Excelsior Motor Company, the motorcycle manufacturing company that his father owned, Robie was just 28 years old when he commissioned Wright to design the home. Chosen for its proximity to the University of Chicago, where Robie’s wife Lora had graduated from in 1900 and was still active socially, the 60 x 180 foot corner lot with unimpeded southern exposure was perfectly suited to satisfy Robie’s design criteria. Abundant natural light, a children’s playroom on the ground floor, and the ability to look out into the surrounding neighborhood without intrusion on his privacy, were a few of the requests that Robie had made to Wright. To put it simply, Robie wanted “a fireproof, reasonably priced home, built to live in – not a conglomeration of doo-dads.”

Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), August 1963. National Parks Service (Public Domain)

The home was completed in 1910, and Robie and his family moved in shortly thereafter. Their stay was short-lived, however. Robie’s father had passed away in early 1909, and Frederick was forced to sell the Excelsior Motor Company to cover business debts that his father had incurred prior to his death. Marital woes soon followed, and Lora Robie and the children moved out of the home in Spring of 1911, and she and Frederick were divorced soon after. The home was sold to David Lee Taylor in late 1911, but after his untimely death occurred within a year of the purchase, the home was again sold in 1912, this time to Marshall and Isadora Wilber. The Wilber family would reside in the home until 1926 when they sold it to the Chicago Theological Seminary (CTS), who inexplicably converted it into a dormitory and dining hall for students of the University.

Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Drawing Sheets 5 and 6 of 14, circa 1933

At an original cost of approximately $55,000 (over $1.4 million today), the home was anything but “reasonably priced,” but what it lacked in affordability, it more than made up for in visionary design and flawless execution. Wright, a master of spatial relations and invoking the emotions of the observer, employs a method of compression and expansion to create an almost palpable sense of drama as one moves from one room to the next.

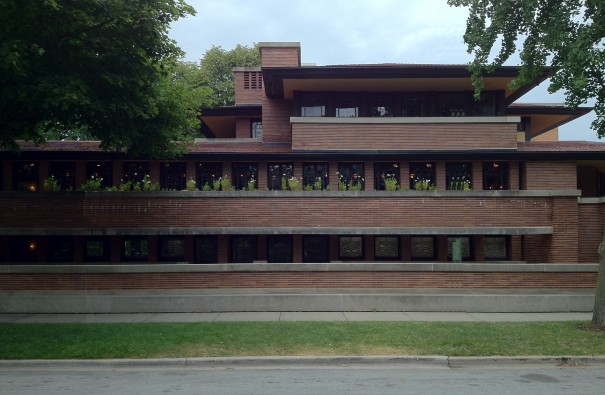

Situated on a narrow, deep lot, the home’s slightly offset pinwheel footprint (above) takes full advantage of its environs. Wright incorporates the lot’s dimensions into the design by making the home over 3 times as long as it is wide, providing the basis for its dominant horizontal Prairie lines. One of the bi-products of this horizontality is the dramatic perspective that’s emphasized when viewing the house along its primary axis (below).

Other subtle ways that the home’s horizontal lines are accentuated include: how the mortar on the vertical brickwork joints was colored to match the brick, while the horizontal mortar was left in its natural color, and the incorporation of a continuous band of art glass windows that runs nearly the entire length of the southern elevation (above).

The band of windows continues above what had originally been a three car garage, but now acts as the Robie House gift shop (above). That same area is now enclosed by an 8 foot high brick wall, creating a private courtyard at the east end of the home. A custom iron gate (half of which is pictured at left) repeats the same pattern that’s found in the all of the art glass windows throughout the house.

The band of windows continues above what had originally been a three car garage, but now acts as the Robie House gift shop (above). That same area is now enclosed by an 8 foot high brick wall, creating a private courtyard at the east end of the home. A custom iron gate (half of which is pictured at left) repeats the same pattern that’s found in the all of the art glass windows throughout the house.

Also visible from the courtyard is one of the two angled alcoves (below) that are situated at opposite ends of the second floor living room / dining room.

Residents of the home would have typically entered and left via an informal entry near the garage (above, at right), while guests would enter from the formal entry at the northwestern corner of the property (below). Consistent with most of Wright’s other Prairie designs, this formal entry is concealed from plain view – a tactic that was employed to force the visitor to assess the building as a whole before entering, encouraging them to notice and appreciate the home’s design and share their opinions of it with homeowner.

While most of those opinions were positive, over the years, enthusiasm for the home waned, and it was threatened by demolition on more than one occasion. Amazingly, the home only functioned as a residence for the first 16 years of its existence, and sadly, not one family has lived in it full-time since it was sold to the Chicago Theological Seminary in 1926. CTS twice announced plans to raze the house in 1941 and 1957, and both times, Frank Lloyd Wright himself was involved in the efforts that ultimately concluded with the home being saved.

Following its designation as a Chicago Landmark by the Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks in 1957, a New York-based development firm, Webb & Knapp, purchased the home in 1958 and later donated it to the University of Chicago in 1962. In April of 1964, the Robie House was declared a National Historic Landmark by the US Department of the Interior, the first such building in the City of Chicago to receive this classification.

Over the next 30+ years, the house was used by the University of Chicago as an office and a meeting space for the Adlai Stevenson Institute for International Affairs, and later by the University’s Office of Alumni Affairs.

Finally in 1997, the Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust entered into an operational partnership with the University of Chicago where the Trust would oversee the day-to-day operation of the house, including hosting tours and events, while the University maintained ownership. The following year, an extensive restoration plan was announced by the Trust, and a massive fundraising campaign was kicked off that would raise millions of dollars to fund the complete restoration of the home and property.

Library of Congress, ILL,16-CHIG,33-6

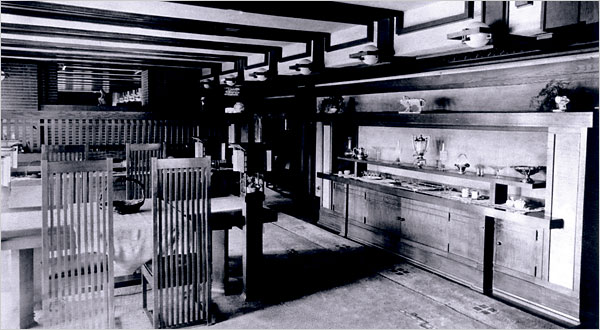

By 2004, the exterior restoration and mechanical systems upgrade had been completed, and work shifted toward the home’s interior. Among the challenges faced on the interior are replicating the woodwork, lighting and furniture that originally existed in the house.

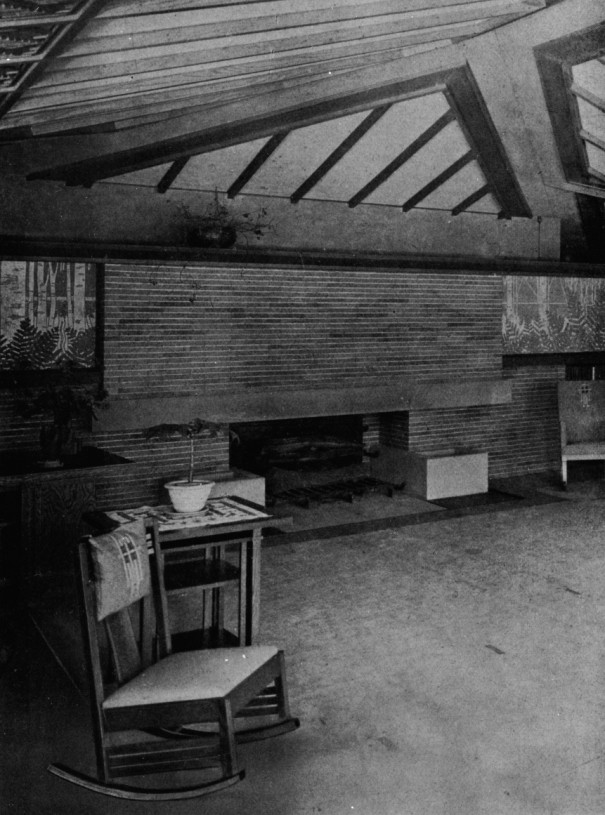

Archival photos have helped with the look and placement of furnishings in the public areas of the home, but very little historical record exists of the bedrooms and other private areas of the home. One such bedroom photo (left) shows the vaulted ceiling and hulking fireplace in the home’s third floor master bedroom.

In the dining and living rooms, an exhaustive restoration has been underway for several years, culminating in return of the home to its original 1910 appearance. The Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust has put together an outstanding website that outlines all of the work that has gone into the project so far. The animated image below illustrates the changes that dining room has undergone during the course of the restoration.

Images Copyright © 2008, Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust

As with every other Frank Lloyd Wright building that I’ve visited, I would highly recommend visiting the Robie House the next time you’re in Chicago. While you’re at it, be sure to check out the dozens of other homes that Wright designed in Oak Park and the adjacent River Forest neighborhood, as well as Wright’s own Home & Studio, where all of his magnificent Prairie Style designs were created.

As with every other Frank Lloyd Wright building that I’ve visited, I would highly recommend visiting the Robie House the next time you’re in Chicago. While you’re at it, be sure to check out the dozens of other homes that Wright designed in Oak Park and the adjacent River Forest neighborhood, as well as Wright’s own Home & Studio, where all of his magnificent Prairie Style designs were created.

3 comments

Historic Kenwood Neighborhood Association says:

Nov 25, 2014

I went there during the restoration. Even then, well worth price of admission. I don’t know how to explain it, other than to say, once you are in the house, you’ll get it. The feel once inside is amazing.

www.intellectarchitects.com.ng says:

Jul 26, 2021

Just researching on the Frederick C. Robie desire by Frank Lloyd wright and this site is a really helpful one I must say.

Frank really did a great deal of work here.

andrew martin says:

May 16, 2022

The house is stunning both in concept and execution. the effects of Compression and expansion are as noted, on full display and do indeed have the distorting effect of spacial augmentation. There can be not disappointment as all the quintessential Wright design and material features are unmistakable, out distancing in all ways the sum of parts. That said, it does not surprise in the least that the home (owners personal circumstances notwithstanding) served only briefly as domicile, as comfort lies acquiescent in all notable ways to design. Case in point is the previously mentioned children’s playroom. Entered via hallway from the garage area and most notable for its unadorned construction values; slab on grade floor, masonry walls and a fireplace, whose defining feature appears to be it pointedly squared poured concrete hearth. There are no soft organic surfaces, no bright windows accessible to curious eyes, only a cold austerity which one would presume antithetic to space designed for children to play in.

The remaining furniture seems likewise unambiguously adherent to geometric inflexibility forgoing considerations physical comfort. The dining set (as well as the three chairs on display on the third floor bedroom) also examples of this resolute purpose.

One can be glad for the fact of the Roby House fortunate continued existence and most grateful indeed for

the opportunity to experience such monumental beauty and clarity of purpose while simultaneously comforted with the sense that it is now in the service of its highest and best purpose.

Thank you very much indeed

martin