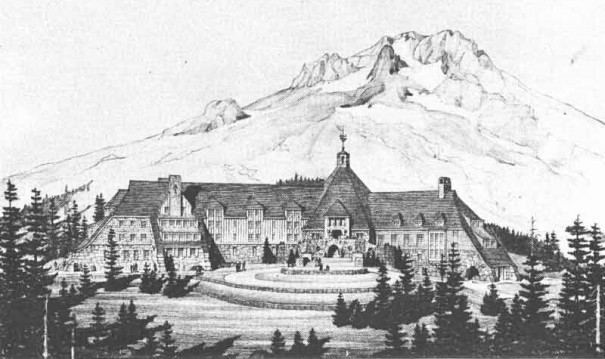

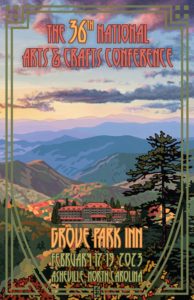

Somewhere near the intersection of rustic charm and stately elegance is a place where natural beauty and cooperative humanity walk hand-in-hand. Nestled a few thousand feet beneath the rugged 11,249 foot peak of Oregon’s Mount Hood, the iconic Timberline Lodge has been welcoming weary hikers, giddy newly-weds – and everything in between – for over 75 years. But its rich history and classic lines would not exist today were it not for a handful of visionaries who first conceived it and later stuck with it in its most dire times.

The idea of building an alpine lodge on the slopes of Mount Hood had seen many incarnations over the years, but the one that was ultimately successful was spearheaded by a well-connected Portland businessman named Emerson J. Griffith. Griffith had been trying for the better part of the 1920’s to garner support for the construction of such a lodge, but when America’s “roaring twenties” – and the excesses that came with it – came to a screeching halt after the Stock Market Crash of 1929, Griffith’s dwindling prospects for securing funding similarly dried up and he feared such a lodge might never be built.

In the years that followed, the country’s financial landscape was transformed from one of wealth and prosperity to one of desperation and poverty. But in 1933, during the deepest pits of this Great Depression, the US Government answered a call to action from its ambitious, newly elected President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and invested in itself, thereby starting a campaign to get America back to work at a time when it needed it most.

Roosevelt’s New Deal kickstarted the movement as numerous federal spending bills swiftly passed through Congress, providing much-needed relief to many sectors of the struggling economy. To that end, in 1934, a bill creating the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was signed into law and two million men and women across the country were soon employed and working on a variety of local and national projects in the public interest. It wouldn’t take long for the ripple effects to be felt in Oregon, and in a fortuitous twist of fate, Emerson J. Griffith was appointed regional administrator of Roosevelt’s fledgling WPA in the spring of 1935.

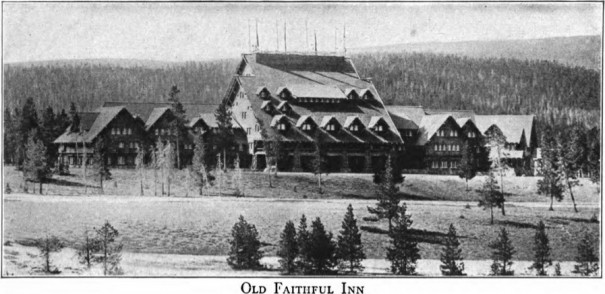

Flush with a windfall of federal money and the authority to spend it, Griffith’s first order of business was, not surprisingly, to move forward with plans to build an iconic mountain lodge on the southern slopes of Mount Hood. Griffith and the Mount Hood Development Association (MHDA), the organization that would operate the lodge once it was built, turned to seasoned architect, Gilbert Stanley Underwood, for the lodge’s design. Underwood had been the principle architect of several other grand lodges in many of the country’s newly minted National Parks, including: Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming (above), The Ahwahnee Hotel at Yosemite National Park in California, and Grand Canyon Lodge (North Rim) in Arizona, among others.

Underwood’s style relied heavily on rustic natural materials and his buildings aimed to highlight the true pioneer spirit of the American West. Incorporating massive logs, cedar shake, intricate stonework and other indigenous materials found near the sites of these grand lodges, his “National Park Style” was heavily influenced by classic Swiss Chalets of the Alps, as well as, the Arts & Crafts Movement, with subtle a nod to the grand Shingle Style homes of the East Coast, to name a few.

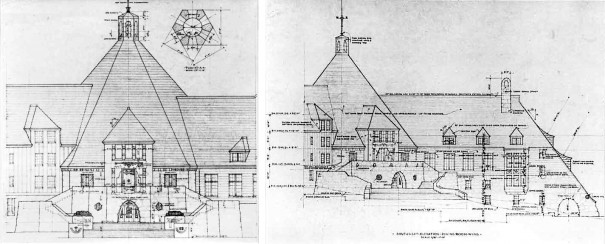

Underwood’s initial design for the lodge (above) consisted of a central octagonal “head-house,” as he called it, flanked by two asymmetrical wings, set off from one and other at a dog-leg angle of 90 degrees. The lodge would face the summit of the mountain with its main entrance at the at the base of the head-house. This design would later be amended by a local architect from Portland named W.I. “Tim” Turner, who had, in fact, submitted his own design for the lodge just weeks before Underwood. The two men differed on their interpretation of just how “rustic” the lodge should be, with Underwood favoring the more utilitarian version with little or no ornamentation , while Turner favored a “more sophisticated” approach with an emphasis on art. Underwood’s design ultimately won out, but not before a number tweaks would be made by Turner.

Turner had more intimate knowledge of Mount Hood and fine-tuned Underwood’s design to take better advantage of the site’s unique attributes. Turner felt that Underwood had underestimated the amount of snowfall that the mountain gets (over 20 feet annually), and siting the lodge to face uphill coupled with a 90º offset between the two wings left it susceptible to prevailing winds and the massive snowdrifts that come with them. Among his many revisions were: changing the octagonal head-house to a hexagonal one, thereby re-aligning the angle of the dog-leg from 90º to 120º, and re-orienting the lodge so that it faced downhill. These alterations and many more – inside and out – would result in the Timberline Lodge that exists today (above).

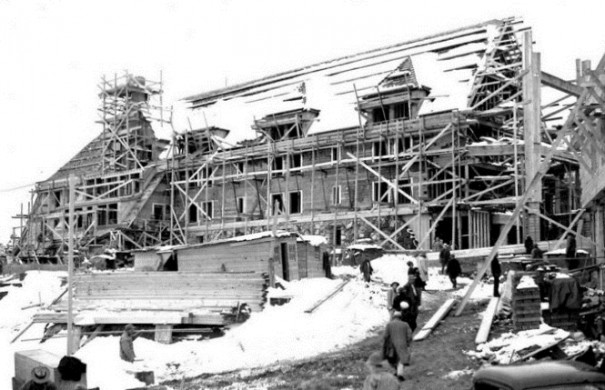

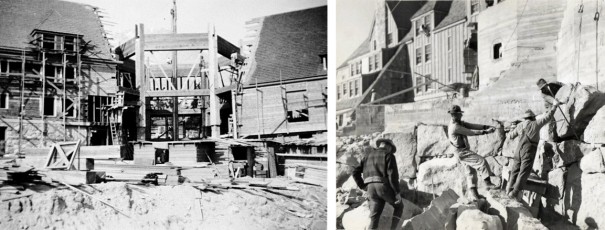

A modest ground-breaking ceremony took place in June of 1936, and amazingly, by August of the same year, the foundation had been laid and the both wings were fully framed. Well over 400 men worked multiple shifts through the long summer days in order to have the lodge completely roofed before the season’s first accumulative snowfall in late Autumn.

Through the fall of 1936, construction at the lodge continued at a swift pace. By early 1937, the exterior – for all intents and purposes – was complete, but there was much to be done inside. Margery Hoffman Smith, assistant state director of the Federal Art Project (the visual arts arm of the WPA), had been brought on board in March of 1936 as the interior design supervisor for the lodge and had been diligently preparing designs while the exterior was being completed. She broke down the interior decor into three main categories: woodwork, ironwork, and textiles, and appointed master craftsmen Ray Neufer and Orion B. Dawson, both of Portland, to direct the first two categories respectively, while Smith herself oversaw the textiles projects.

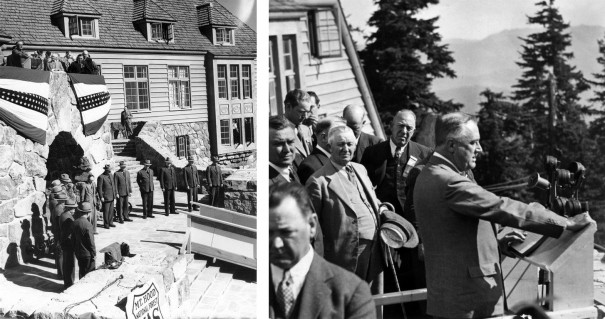

Of course, all of this was made possible by Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration and the men and women it employed, and as construction neared completion, the President would soon have the opportunity to witness the fruits of their labor firsthand.

On September 28, 1937, Roosevelt himself stood on the steps of the Lodge and addressed a sizable congregation with his dedication:

“I am here to dedicate Timberline Lodge…as a monument to the skill and faithful performance of workers on the rolls of the Works Progress Administration…not only as a new adjunct of our National Forests, but also as a place to play for generations of Americans in the days to come… The people of the United States are singularly fortunate in having such great areas of the outdoors in the permanent possession of the people themselves.”

Timberline Lodge officially opened its doors to the public in early 1938, and for the next few years, business was brisk as tens of thousands of people came from far and wide to stay at the newly completed lodge. However, with the onset of World War II, visitation dropped off quickly, and by the summer of 1942, business was down 50%. So immediately after Labor Day of that year, the MHDA, who had been running the day-to-day operations since it opened, decided to close the lodge for the duration of the war.

Upon its re-opening in late 1945, and over the next 10 years, the lodge was poorly managed by a number of different entities, and even had to be closed again at one point because the power bill hadn’t been paid. Finally in 1955, Richard Konstamm took over managing the lodge, and in just three short years, the lodge was once again profitable. Konstamm was a visionary who saw the lodge as the centerpiece for a world-class ski area, and worked tirelessly to develop the terrain. By 1962, demand was such that a new Miracle Mile chair lift was built that quadrupled the capacity of its predecessor. Under Konstamm’s guidance, additional amenities, including several more lifts, a year-round swimming pool and a full convention center wing were added, and the lodge has thrived ever since.

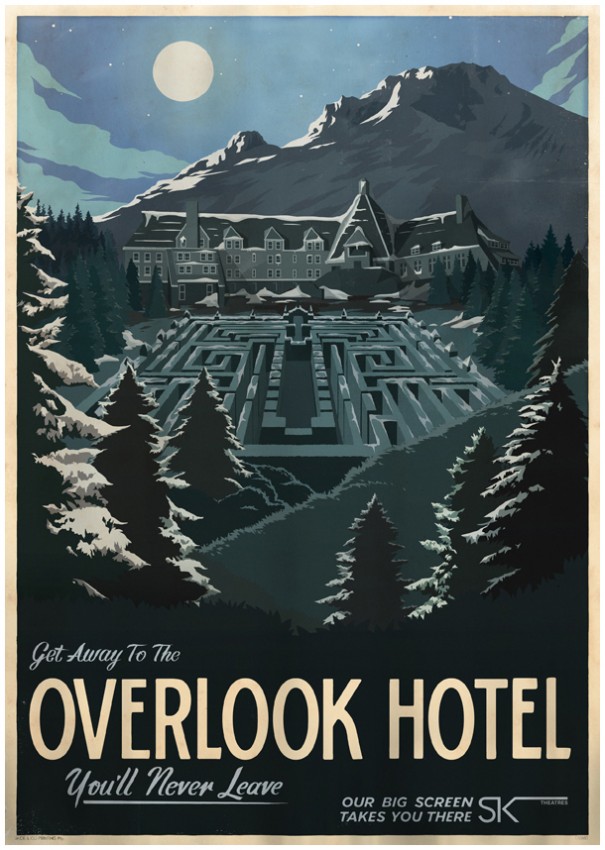

Over the years, the lodge also gained considerable notoriety by being the backdrop for multiple Hollywood films. The most famous, of course, being Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film adaptation of Stephen King’s masterpiece The Shining, where the lodge was cast as the fictional Overlook Hotel. The lodge was used for the exterior shots in the film, but what you might not know is that the interior is nothing like what is portrayed in the film. In fact, the interior scenes were filmed on a London soundstage that was modeled after another of Stanley Underwood’s hotels, the Ahwahnee Lodge in Yosemite National Park. There is also no labyrinth at the hotel, that too, was created for the movie on a set in London.

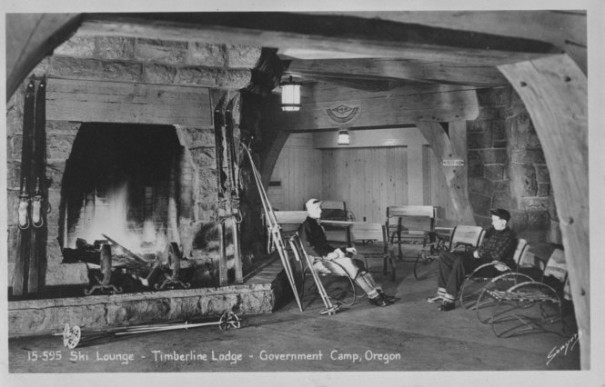

The real interior of the lodge is absolutely captivating and epitomizes, in my opinion, what a mountain ski lodge should look like. Stay tuned for Timberline Lodge: The Quintessential American Alpine Lodge, Part Two, where I’ll take you on a guided tour through the halls of this unique and timeless lodge. But for now, I’ll leave you a taste of what’s to come…

![]()

Please read the continuation of this article Timberline Lodge: The Quintessential American Alpine Lodge, Part Two, in which I’ll take you inside this storied lodge on a personal tour through its hallowed halls…