This article is Part Two of a two part series highlighting the homes that Frank Lloyd Wright designed in Oak Park, Illinois during the years 1900 to 1913. Part One focused on his transition to the Prairie Style and the Oak Park homes he designed from 1889-1899.

During the years of 1889 to 1899, Frank Lloyd Wright’s style was mainly influenced by the existing architectural modes of the day, as well as his experience from working in Chicago at Adler & Sullivan, but by the close of the decade, an expression of a new style – the Prairie Style – would begin to emerge. In the decade that would follow, Wright’s aesthetic would continue to evolve, and the homes that he designed in Oak Park during the years of 1900-1913 would be at the forefront of the Prairie Style movement that he helped champion.

The Prairie School, as it has come to be known, had its roots in 1896 where a workspace in Chicago’s Steinway Hall was shared by several emerging architects, including Wright, Myron Hunt, Walter Griffin, and Dwight Perkins, among others. Like the Arts & Crafts Movement, the Prairie School was an adverse reaction to the Industrial Age, and “The Chicago Group,” as they were sometimes referred to, yearned to develop a new, uniquely American style that wasn’t influenced by any of the numerous European Revival styles that were de rigeur in the early 1900’s.

The “Prairie” name attached to the style was not coined by Wright, or even any of his contemporaries, it’s attributed to H. Allen Brooks, an architectural historian who would write about the style decades later. The term was meant to describe the dominating horizontal emphasis that the style exhibited, and its likeness to the flat, undulating landscape of the prairies in the American Midwest. But beyond that, the style encompassed several other traits that can typically be found in homes or buildings that bear its name. These include: hipped roofs, deeply overhanging eaves, finely detailed art glass windows often grouped in long horizontal bands, and a general lack of excessive exterior ornamentation.

In 1898, Wright moved his practice from Steinway Hall in Chicago to his newly constructed home studio in Oak Park (above, right), and in doing so, he was able to concentrate more closely on the many projects he was working on in his home neighborhood. Taking cues from some of the motifs that he had been experimenting with in the late 1890s, Wright’s first full-fledged Prairie design came to fruition with the Frank W. Thomas House in 1901.

Not long ago, I visited 22 of the homes that Wright designed in Oak Park and compiled the interactive map below. You can click on the blue placemarks to see the address of each home along with a photograph that I took of it. Click here for a larger version of this map.

![]()

View Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park Home Designs in a larger map

Below you will find the continuation of the list of the 22 homes that I visited on my self-guided tour of Oak Park – starting with #11. These twelve buildings represent those that Wright designed in Oak Park during the years of 1900 to 1913. They’re listed in chronological order based on the year they were designed by Wright.

NOTE: With the exception of Wright’s Home & Studio and The Unity Temple Church (#16 on this list), all of these homes are private residences, so please respect their privacy and do not trespass or otherwise disturb the owners.

![]()

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park Designs: 1900-1913

11. E. Arthur Davenport House (1901) – 559 Ashland Ave

At first glance, the Davenport House does not appear to have been designed in the Prairie Style, but with the exception of it’s gabled roof, all of the tell-tale signs are indeed there. Although the home’s façade was altered in 1931, the home as it looks today (below) has been restored to its original appearance. It’s essentially an inverted version of a spec

house that Wright designed (below) which was published in the July 1901 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal. About the home, Wright had written, “the average homemaker is partial to the gable roof. This house has been designed with a thorough, somewhat new treatment of the gable with gently flaring eaves and pediments, slightly lifted at the peaks, accentuating the perspective, slightly modeling the roof surfaces, and making the outlines crisp.”

Wright designed two other homes with this type of roofline, the Bradley House and the Hickox House, which are located next door to one and other in Kankakee, Illinois.

![]()

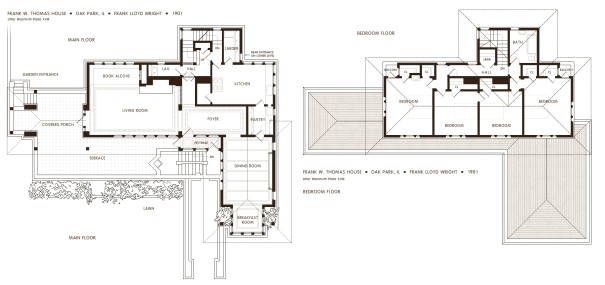

12. Frank Wright Thomas House (1901) – 210 Forest Ave

Widely acknowledged as Wright’s first full-fledged Prairie Style home built in Oak Park, we finally see the culmination of over a decade’s worth of experimentation and honing. All of the hallmarks of the Prairie aesthetic are presented here in an organic, cohesive form that is pleasing to eye. The arched entry at center is not the front door, but rather leads into a tiny courtyard where access to the front door is gained after turning left and climbing a stairway.

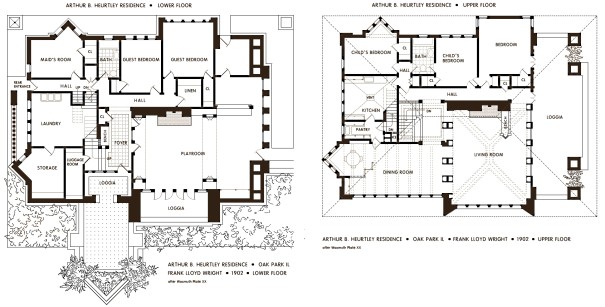

There are three floors in the home, with the partially submerged ground (or basement) floor originally used as servants’ quarters. The family’s living quarters encompass the upper two floors (below) with all four bedrooms being arranged in a line on the top floor – a design characteristic that would re-surface in many of Wright’s later Usonian designs.

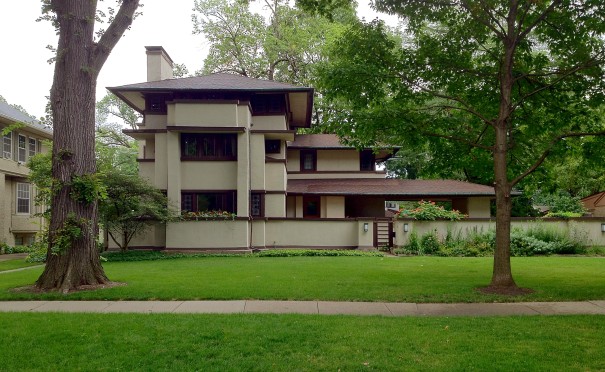

13. William G. Fricke House (1901) – 540 Fair Oaks Ave

The dichotomy of the William G. Fricke House (also known as the Emma Martin House, circa 1906) is that while its Prairie elements focus on highlighting its horizontal features, the home’s design is unequivocally vertical. While being anchored by a soaring three-story central tower (below), Wright gracefully employs layers of cascading rooflines and horizontal exterior bands to help draw one’s attention away from the home’s height.

When I first approached the Fricke House, I was captivated by this unorthodox dichotomy as my eyes struggled with what to look at first. Even among all the other Wright homes in Oak Park, in my opinion, this one stands out. If you think about what typical residential architecture looked like in 1901, this home would have been a radical departure from what the casual observer was used to seeing. Unfortunately for Mr. Fricke, he was only able to enjoy it for a short while, as divorce and later financial troubles forced him to sell the property to Emma Martin in 1906. Martin wasted no time hiring Wright to design a garage for the home (below, at left), and a wall connecting the two buildings was later added. A covered veranda on the south side of the original home was demolished some time ago when the lot was sold and later developed. For more exterior photos, please visit here.

14. William E. Martin House (1902, Pergola 1909) – 636 N East Ave

As with its predecessor, the Fricke House (above), the William Martin house exhibits an undeniable vertical prowess, but through Wright’s brilliant design execution, the home’s height is again considerably downplayed. Incidentally, this would be Wright’s last three-story Prairie design. Also worth noting was that this home’s original owner was the brother of Darwin Martin, for whom Wright would design an expansive complex in Buffalo, New York a few years later.

15. Arthur B. Huertley House (1902) – 318 Forest Ave

With the Heurtley House, we see Wright’s Prairie Style continuing to mature. The refined, monolithic façade is reminiscent of the Winslow House (FLW, 1894), with it’s arch detail and massive central fireplace. But here, Wright has put more of an emphasis on horizontality with long bands of windows and a brick treatment that called for the vertical mortar joints to be dyed the same color as the brick itself – thereby obscurring them – while the horizontal mortar joints were left in their natural color. Additionally, alternating layers of brick were laid slightly proud of the rest of the surface, creating more horizontal bands.

Another unusual feature of the home is that Wright put the living quarters – the kitchen, living room and dining room – on the second floor, a characteristic he would continue to use in other Prairie designs, including the Frederick C. Robie House (1906). All of the home’s six bedrooms are situated at the rear, providing privacy from the street. Over the years, numerous owners (including Wright’s own sister) have altered the original design, but when the home was sold in 1997, its new owners painstakingly restored it to its original condition. A great collection of archival photos of the home’s interior can be found here.

16. Unity Temple (1902) – 875 Lake St

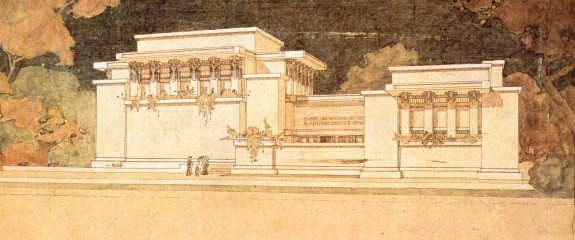

One might expect that the exterior of a building made entirely of reinforced concrete might be rather drab, but in the case of the Unity Temple, quite the opposite is true. Wright’s design consists of a congregational gathering building (below, left) along with a community space and school (below, right), connected via a single story intermediary lobby. This Prairie Style building included columnar ornamentation reminiscent of Wright’s early mentor, Louis Sullivan, and was one of his earliest implementations of a flat roof.

17. Peter A. Beachy House (1906) – 238 Forest Ave

Although the Beachy House is technically considered a “remodel,” the only remnant of the original Gothic style home that exists is part of the basement foundation, and none of it is visible on the exterior. His first commission upon returning from a trip to Japan, Wright chose to adorn this Prairie Style home with seven gables, perhaps a nod to the Asian architecture he encountered on his trip. Wright also designed much of the furniture for the home, some of which is still in use today by its current owners. Like its neighbor the Nathan Moore House, the home is situated on the extreme northern edge of the property, leaving a wide expanse to take better advantage of southern exposure to sunlight.

18. Isabel Roberts House (1908) – 603 Edgewood Place, River Forest

One of the most advanced examples of Wright’s use of the cruciform floor plan to date, this home was designed and built (on a limited budget) for one of Wright’s draftspeople (who would go on to become a notable architect in her own right), Isabel Roberts. Of note is the sunken two-story living room with floor-to-ceiling windows and the second floor balcony that overlooks it, as well as the accommodations that were made to allow a growing British Elm tree to penetrate the roof of the south porch. Isabel lived in the home with her mother, Mary, for several years before moving to Florida around 1915 when Mary’s health deteriorated. The home was renovated in 1922 by fellow Wright draftsman, William Drummond, and updated again by Wright himself in 1955, where he employed some of his later Usonian ideals.

19. J. Kibben Ingalls House (1909) – 562 Keystone Ave, River Forest

Wright was particularly fond of this unusually symmetric home that he designed for his good friend Kibben Ingalls. A floor plan based on a Greek cross enabled Wright to satisfy his client’s request that every room have windows on three sides. The omnipresent central fireplace is flanked by the entry on south side and the dining room on the north; the living room extends out of the front of the home to the east where it gracefully collects unencumbered morning sun. Upstairs, balconies extend from bedrooms on both sides, while the master bedroom looks out over the front lawn. Ingalls lived in the home until he passed away in 1937, and his wife remained until her death in 1950. The home now belongs to a Chicago architect who has worked on several other Wright-designed homes. Minor modifications to the home have been made, while still respecting its historic heritage.

20. Mrs. Laura R. Gale House (1909) – 6 Elizabeth Court

Laura Gale, widow of Thomas Gale, for whom Wright designed two nearby homes in 1892, commissioned this home on property that she acquired following the death of her husband in 1907. The construction date was 1909, but there are conflicting reports regarding when Wright actually designed the home, which may have been as early as 1904. Significant for its slab roof, multiple cantilevers, and rectangular massing, Wright later acknowledged that he explored themes with this home that he would expand upon decades later with his masterpiece, Fallingwater. To see the floor plan of this home, click here.

21. Oscar B. Balch House (1911) – 611 N Kenilworth Ave

As the story goes, Wright abandoned his wife and family in 1909 and ran away to Europe for a year with his mistress, Mamah Borthwick Cheney (who also happened to be the wife of a previous client, Edwin H. Cheney). The Balch House represents one of the first commissions he received upon his return to the United States in 1911. Like the Laura Gale House (above), the Balch House has a flat roof and a protruding parapet surrounding a ground floor terrace. A nearly continuous band of art glass windows spans the entire street-facing façade, which is then capped by the thin brow of the flat roof.

22. Harry S. Adams House (1913) – 710 Augusta Ave

The Adams House represents the culmination – as well as the termination – of the homes that Frank Lloyd Wright would design in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois. The now fully matured Prairie Style is exhibited here with its wide longitudinal stance, hipped roof, brick exterior finish, and porte-cochère (the only one of Wright’s Oak Park homes to have one). Vaguely reminiscent of the Darwin Martin House in Buffalo, this design was actually the third that Wright prepared, after the first two were rejected by Adams due to their cost.

The twenty years that Frank Lloyd Wright lived and worked in Oak Park were among his most productive. Those years saw the prolific architect transition away from designing homes and buildings in traditional variations of existing styles, and develop the groundbreaking Prairie Style for which he is universally known. While he designed dozens of homes for clients in his own neighborhood, there were many more projects that were commissioned by clients across the country during this same period. It was during this early prolific period of Wright’s career that he established himself as one of the most highly sought after architects in the country.

Oak Park, Illinois is located less than 10 miles from downtown Chicago and is easily accessible by mass transit. For more information about visiting Frank Lloyd Wright sites in Oak Park and the greater Chicago area, including his Home & Studio, The Frederick C. Robie House, and The Rookery, please visit: www.FLWright.org

If you’ve already visited one or more of these sites, I’d love to hear from you, so please leave a comment below!

3 comments

Matt Horvath says:

Apr 4, 2014

On the Laura R. Gale House, while she was on a trip to Michigan, her horrified neighbors contacted her exclaiming “that she should come back to see this terrible thing that Wright was building on her lot!”

shrishti says:

Feb 20, 2016

Does all the buildings of wright shows organic influences??

Theresa Dickison says:

Jul 19, 2016

I recently went on one of the Oak Park Pedal tours that the FLW trust gives and it was fantastic. I highly recommend it. We saw every one of the houses (from the outside) and our guide was pretty knowledgeable about all of them. Just walking around Oak Park is mindblowing from an architectural standpoint; not just for the FLW houses but for ALL of the houses.