Frank Lloyd Wright grew up in the Upper Midwest and honed his skills as an apprentice with the prestigious Chicago architectural firm of Adler & Sullivan in the 1890’s, before branching out on his own. At the turn of the 20th century, Wright had completed over 50 projects and began to develop his groundbreaking “Prairie Style”, for which he is universally known.

One of the earliest and most dramatic examples of Wright’s newly evolved Prairie Style is the magnificent Darwin D. Martin House (above), located in the Parkside neighborhood Buffalo, NY. The house was a precursor to one of Wright’s other high-profile Prairie Style designs, The Frederick C. Robie House built in Chicago in 1908. I’ve toured the Martin House twice – once in summer and once in winter – and it’s equally enthralling at anytime of year. Darwin Martin, who was an executive at the Larkin Soap Company (where Elbert Hubbard was also an executive), knew of Wright’s work from his brother William, who in 1902 commissioned Wright to design a home for him in Chicago’s Oak Park neighborhood.

When Darwin visited Chicago and saw the home that Wright had designed for his brother (above), he knew right-then-and-there that he had found the “Wright” architect to design his own home back in Buffalo.

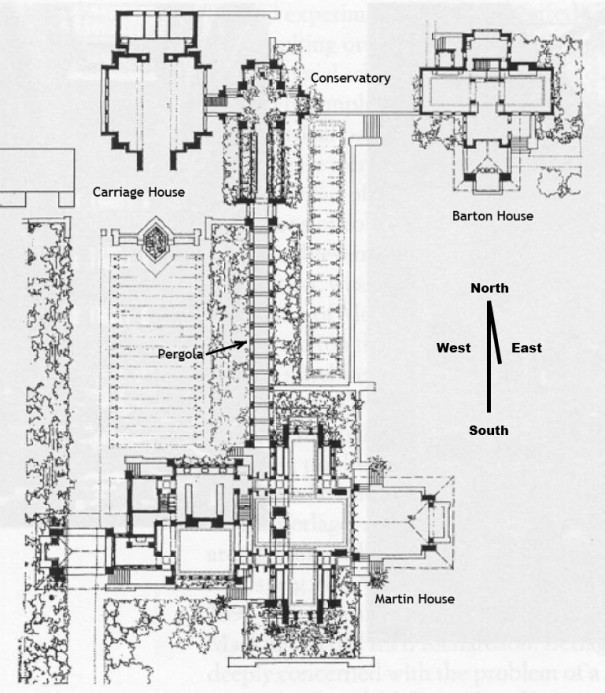

For the Darwin Martin House, Wright was presented with a large corner lot on which to build, and he took advantage of nearly every square inch of it.

In the original 1903 design, the main house was surrounded by several ancillary structures including: The Barton House, The Carriage House (originally built with horse stables), The Conservatory, and a 100 foot long semi-enclosed Pergola which connects The Conservatory with the main house – The Gardener’s Cottage was later added in 1909.

The Barton House (above) was built for Martin’s sister, Delta, and her husband, George F. Barton. It was the first building built in the Martin House Complex and also the first built by Wright in Buffalo.

The Carriage House (above left) and the Conservatory (below left) are connected via a short hallway. A full-size cast of the Winged Victory of Samothrace statue stands at the far end of the conservatory (below left) and looks back through the pergola toward the main house (below right). The original statue, which was carved by an unknown artist around 200 BC and at some point thereafter, lost its head and arms, is housed in the Louvre in Paris.

The pergola (above right) bridges the distance back to the rear of the main house (below) and frames a courtyard lined with walkways and flower beds.

The Gardener’s Cottage (below) was added in 1909 and is where the Martins’ gardener, Reuben Polder resided. In addition to maintaining the grounds and looking after the plants in the conservancy, Polder was tasked with bringing fresh flowers daily to every room in the home.

The main house was built between 1904 and 1905 and at approximately 15,000 square feet on three levels, it’s a massive structure. However, by breaking up the house into rooms with varying ceiling heights, layered roofs, and very few large flat walls, Wright’s design makes it feel much more intimate than that.

The “Prairie Style” was so-called because it emphasized horizontal lines and multiple subtle hip roofs that mimicked the flat, gently undulating prairies of the Midwestern United States. Even though this home is in increasingly less-flat Western New York, the large open lot on which it sits lends itself well to the Prairie aesthetic.

The large banks of windows keep the rooms well-lit, even though the roof’s large over hanging eaves often shade the interior from direct sunlight.

In what would become a common characteristic of many of Wright’s designs, the front door is tucked away and difficult to see as you approach the home. In the image above, the front door is concealed in the far corner – behind, and to the left of, the large planter near the stairs.

The property’s hulking eastern elevation (below) is surrounded by the continuing half-wall and more large planters, as well as an inviting covered porch off the living room.

The western side/rear elevation (below) features another concealed entrance and a symmetrical bank of windows that mirrors the front of the home.

This partial northern elevation (below) looks toward the home and its first floor kitchen from the courtyard along the pergola (on the left).

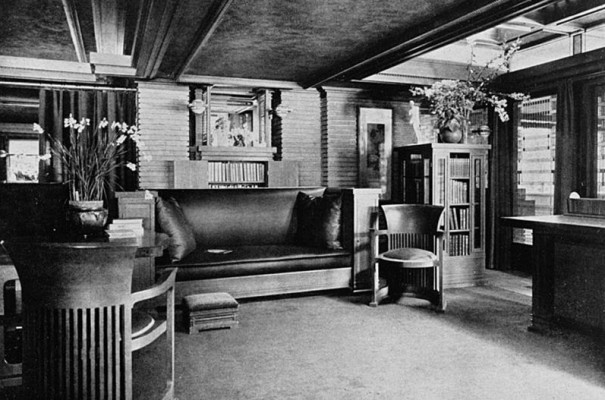

Unfortunately, photographs aren’t permitted on the interior of the house, so the images you’ll see below are courtesy of the Library of Congress.

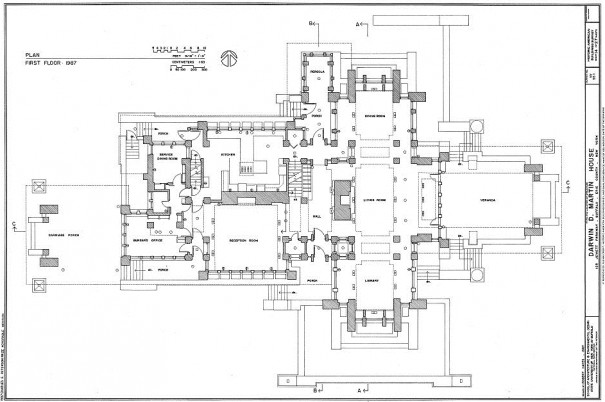

In the first floor plan (above), you can see how Wright’s limited use of large walls and doors yields an open format while still respecting the traditional elements of the home – the entryway, living room, dining room and kitchen. For a larger version, click here.

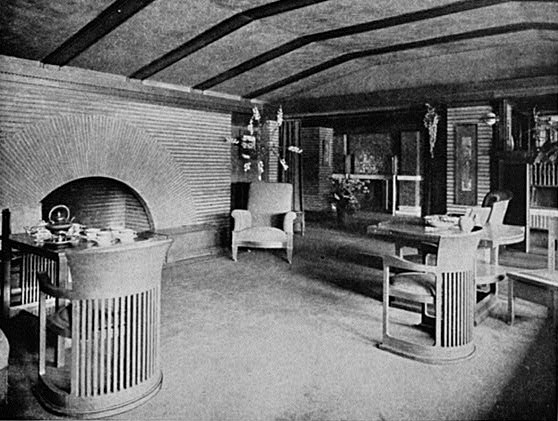

The Reception Room (above) is off to the left of the main entryway. It’s known for its barrel-shaped ceiling and it’s grand “sunrise” fireplace. The furniture pictured is original and although very little of it remains today, much of it has been impeccably reproduced.

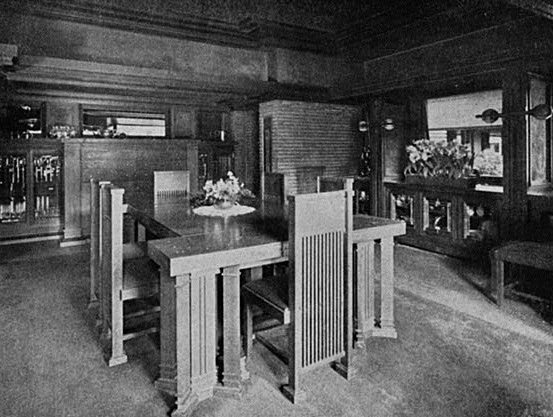

Part of the design package mandated that Wright designed the furniture, windows, art glass, and textiles for the home. These tall-backed chairs in the dining room (above) contrasted the home’s horizontal lines and created a feeling of intimacy for the Darwins and their guests at mealtimes.

As in much of the rest of the home, the ceiling height varied in the living room (above) and contributed to breaking up the large rooms into smaller, more casual vignettes.

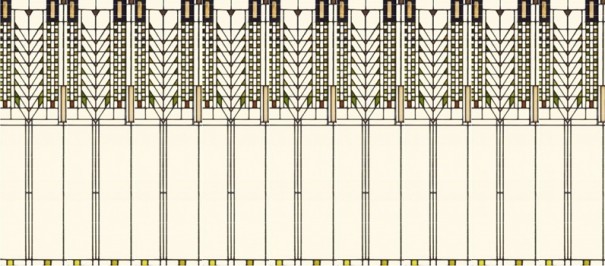

Most of the rooms in the Martin House feature stained glass windows, and the pattern in the image above is repeated throughout the home. Wright was not fond of curtains in the homes he designed and preferred to use art glass to provide privacy for his clients.

Darwin Martin lived on the property for 30 years. He had amassed a sizable fortune from his work at the Larkin Soap Company, but following the stock market crash of 1929, Martin lost nearly everything. He remained at, and ultimately died in the house in 1935 following a series of strokes.

In the years following his death, his family could no longer afford to maintain the property and abandoned it in 1937. Surprisingly, for the better part of the next 20 years, the home remained vacant and suffered considerable damage from lack of maintenance and vandalism. In the mid 1950s, the property was finally sold and the main house was split up into apartments while sadly, the Carriage House, Conservatory and Pergola were all demolished in the 1960s to make way for an apartment complex.

In 1967, the home was sold to the University of Buffalo and used as the President’s residence. The University was instrumental in having the property added to the National Register of Historic Places and it was ultimately deemed a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

In the mid 1990s, The Martin House Restoration Corporation was formed with the intent of reacquiring the property and restoring it back to its original condition. Thanks to the tireless efforts of its members and volunteers, over the next several years, the MHRC began purchasing the property back and by 2007, the Carriage House, Conservatory and Pergola had all been meticulously rebuilt to Wright’s original design specifications. It’s been a massive undertaking, and having visited the property twice now, I can say without hesitation that you would never know the new structures were not original.

The Greatbatch Pavilion, a large mostly glass visitor center has been built immediately adjacent to the house and has lots of great historical information to check out while you wait for your tour to begin. Tours are offered daily and the proceeds go toward the continued restoration of the property. During my last visit, work was still going on in the entry and kitchen, so I’m anxious to get back soon and see the finished product.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT / DARWIN MARTIN HOUSE [MONTAGE] by Jonathan Turner.

If you don’t have a chance to visit, above is a fantastic montage video of the Martin House by New York based artist and director Jonathan Turner that just might convince you to make the trip. It dramatically and emotionally highlights many of the finer details and geometric lines that give this house its unique style.

It really is an amazing place, and I would encourage anyone who’s in the Buffalo area to visit. In addition to the Darwin Martin House, Frank Lloyd Wright designed several other buildings and private homes that are nearby – including The Graycliff Estate, the summer home that Wright designed for Martin’s wife, Isabell. I’ve visited all of them and have written about them here…so check it out and let me know what you think!

1 comment

David J Gill says:

May 23, 2016

I visited the Martin house in 1979 or 1980 when a few grad students lived there as caretakers. The house then was stripped and empty; the nursing home built on the site of the conservatory was still in operation. We mused about restoration one day and all agreed it was the sort of thing for which the money would never be found. What is the story of where the impetus came from and how the funds were found to do this amazing resotation, now mostly complete?